Build a Team, Not a Family: The Operating Model Behind 10x Startups

If you want to win by a mile, you can't run your company like a family. Here's what "Olympic-level" standards actually look like in a startup.

Every company says they want A players.

Every company says they want to move fast.

And yet, most teams operate like the expectation is participation, not domination.

Startups don’t get the luxury of slow.

Big companies can be inefficient and survive because they have time, brand, and resources.

We don’t.

This is for my colleagues.

For the people joining our team.

And for the teams I would want to join myself.

It’s a written version of the standard I expect, not because intensity is fun, but because the mission requires it.

If you want a job that is comfortable and predictable, this post will feel like too much.

That’s not a diss.

It’s just clarity.

One more thing before we start.

You’re going to see me repeat myself.

Not because I’m out of ideas.

Because the most important ideas deserve repetition.

So let me be clear about what I mean when I say build a team.

I’m not talking about a friendly group chat.

I’m talking about an Olympic level, professional level team.

The kind of team that expects to win every game, every season, not by an inch, but by a mile.

If that sounds intense, good.

Because it is.

And the real question is simple.

Do you actually want to be the best?

I: Team vs family (and why this matters)

This is not about being cold.

It’s not about people being disposable.

It’s about being honest about what we’re optimizing for.

A family is built on unconditional belonging.

Families stick together.

Families don’t leave people behind.

There’s leniency baked in because the bond is the point.

A team is built on a shared mission and a shared standard.

Care, respect, dignity, coaching, and support still matter.

But the bond is not that we are related.

The bond is this.

I trust you to deliver.

So when you say I got it, I don’t have to question it.

Not because you’re perfect.

Because you’ve built the habit of excellence.

And because the work is hard enough already.

The goal is to spend our energy on the objective, not on negotiating differences in work ethic.

II: The anti-vision (what happens when you run a startup like a family)

Running a startup like a family sounds nice.

Until the first decision shows up that hurts right now.

There’s a moment every team hits.

A role is no longer a fit.

A skill set is no longer enough.

A player is no longer right for the game you are now playing.

And you know it.

I’ve flinched here before.

It never gets easier.

It gets slower.

But ripping the band-aid off today feels too painful.

So you wait.

You keep the not-ideal fix in place.

You tell yourself it will stabilize.

You tell yourself you will deal with it next quarter.

What actually happens is worse.

High achievers start routing around the blocker.

They take on extra load.

They feel the drag.

Then they get angry.

Not because the person is bad.

Because the standard is no longer being protected.

This is how you get death by a thousand paper cuts.

Not one catastrophic mistake.

A hundred small delays.

A hundred decisions not made.

And the second-order effect is the most dangerous one.

The people you most want to keep are the first ones to leave.

That’s how you lose.

Not from lack of effort.

From lack of clarity.

III: Hyper-transparency is the fix

One of the best examples of hyper-transparency I’ve ever seen was at Legion Technologies in 2019.

We were a sub-50 person company, and the founder, Sanish Mondkar, ran weekly all-hands with metrics and highlights on what was happening across the business.

And once per quarter, he’d share the deck that went to the Board of Directors.

Not summaries.

The real deck.

At the time, I was early in my career and didn’t fully appreciate how rare this was.

Strategically, we were moving upstream from SMB to Enterprise.

That meant running two companies in parallel.

Keeping the SMB motion healthy.

While building a brand new Enterprise playbook at the same time.

Without transparency, that kind of transition tears teams apart.

With transparency, people could see the game early enough to adjust.

They could build new skills before it became a crisis.

That’s not cold.

That’s leadership.

IV: Winning by a mile

There are two very different arenas companies compete in:

- The “close enough” arena: most options are comparable, features barely differentiate, and the risk of choosing A over B is basically the same as choosing B over A.

- The “win by a mile” arena: your only real competitor is the last version of you, and the second-best option starts to look irrational.

When you’re in arena #2, you stop benchmarking your competitors.

You benchmark your potential.

One of the best examples comes from Nvidia.

Jensen Huang has described a doctrine often summarized as “competing at the speed of light.”

He refuses to benchmark against competitors.

Instead, projects get judged against the theoretical maximum allowed by physics.

Not are we faster than them.

But are we as fast as reality allows.

His belief is simple:

If you only try to beat competitors, you breed mediocrity.

If you compete against yourself, you prevent internal rot.

Because Nvidia’s worst enemy is not the market.

It’s complacency.

V: Game time vs practice time

In football, game time is what happens under the lights.

In a company, game time is what happens during the obvious hours: the meetings, the builds, the calls, the launches.

But the teams that win by a mile don’t just show up to games.

They practice.

Practice is what you do before and after game time.

In the startup world, that’s often outside “normal business hours.”

For some people, that’s 9-to-5.

For us, practice is what happens before you show up, and after you get home.

It’s the reps nobody claps for.

It’s the boring work that makes the hard moments look easy.

It’s being obsessed with honing your craft.

Not because hustle is cool.

Because being best-in-class isn’t an accident.

If you want to be best in class, you don’t treat practice like an optional hobby.

You treat it like the job.

VI: The 2-minute drill

The 2-minute drill isn’t working harder.

It’s working under constraint: limited time, high stakes, zero room for confusion.

In sales, that’s end of quarter.

In product and engineering, it’s launch week, customer escalations, major incidents.

Those moments don’t create capability.

They reveal it.

If you’ve done the reps, you look calm.

If you haven’t, you look surprised.

And surprise is expensive.

VII: Earn your spot every day

No one is the starter forever.

You earn your spot daily.

Not through activity.

Through outcomes.

What did you do that moved the ball forward?

Not what did you do today.

What changed the scoreboard?

If you join a professional team but treat it like a casual league, the expectation is not shame.

The expectation is replacement.

Not out of fear.

Out of excellence.

Because everyone on the team deserves teammates who respect the standard.

VIII: The tests (run these on your team)

Here are a few tests I use to tell whether we are actually building a team.

1) The “I got it” test

When someone says I got it, do you feel relief, or do you feel the need to follow up?

On elite teams, I got it means this:

- It will get done.

- It will be high quality.

- It will be on time.

- It will not require babysitting.

2) The 2-minute drill test

When things get compressed (launch week, incidents, escalations), does the team get quieter and faster, or louder and slower?

Crunch time reveals the reps.

3) The 6-month test

If you looked around the org in six months, would you still be able to get hired here?

If the answer is obviously yes because you still feel like the smartest person in the room, the baseline didn’t rise.

IX: Pressure, coaching, and context

There are two kinds of pressure that matter on elite teams.

Pressure to be obsessed with figuring it out.

Pressure on the outcome, then freedom on the path.

I’m a believer in the second.

But only if leadership does its job first.

There’s a failure mode I’ve seen many times.

A leader demands an outcome.

The team misses.

Everyone assumes the problem is execution.

More urgency.

More pressure.

More micromanagement.

Sometimes that’s right.

But sometimes the miss has nothing to do with effort or talent.

It’s a context failure.

I have watched extremely strong people miss badly because they were solving the wrong problem.

Not because they were careless.

Because they didn’t have three things leaders often forget to provide:

- Coaching (how to level up in this situation)

- Context (why this outcome matters more than the others)

- Information (what constraints exist that they cannot see)

Without those, smart people still work hard.

They just optimize the wrong thing.

And then we burn cycles arguing about execution.

When the real failure was leadership.

X: Hiring for leverage

On professional teams, you don’t want everyone to be pretty good at everything.

You want people who are spiky.

Deep specialists.

Best in class in the role they are in.

In sales, some people are elite at generating pipeline.

Some people are elite at closing.

Both are valuable.

Confusing them creates chaos.

The job is orchestration.

Put the right spikes together and make the handoffs clean.

That’s how a team becomes 10x.

Talent density

Talent density isn’t a flex.

It’s a speed strategy.

Low talent density creates a hidden tax:

- More follow-ups

- More re-explaining

- More rework

- More “management” for problems that shouldn’t need managing

And the worst part is who pays that tax.

Your best people.

They start routing around the bottleneck.

They carry the extra load.

And eventually they leave.

High talent density flips the default.

You get to spend your energy on the objective, because the baseline is assumed.

Barrels vs ammunition

Here’s the hiring failure mode I see over and over.

You hire for relief.

I’ve made this hire.

It feels good for a week.

Then it becomes your job.

The work is piling up, you’re tired, and “good enough” starts to look attractive.

So the question quietly shifts from:

Is this person elite?

To:

Is this the best we managed to find?

And then the cost shows up immediately.

More coaching.

Less initiative.

More managerial work.

Keith Rabois calls this “barrels and ammunition,” and it’s one of the cleanest ways to explain why some teams move faster than others. He helped build PayPal, LinkedIn, and Square. (First Round write-up)

This is the difference I watch for:

A barrel can take a messy problem from blank page to shipped outcome.

They create clarity.

They ask for what they need.

They execute.

They communicate.

Ammunition is talented too, but it needs a barrel pointed in the right direction.

In a resource-constrained startup, you can’t hire management debt.

You need leverage.

Outcomes.

Not administration.

XI: The reps (film review)

Practice is not abstract.

In sales, practice looks like reviewing past calls, running demos, grading yourself honestly.

In product and engineering, practice looks like pre-mortems, post-mortems, and cleaner interfaces.

People say they want to move fast.

This is how you actually do it.

XII: The protocol

Standards don’t hold themselves.

You need mechanisms.

A simple weekly operating system looks like this:

- Scoreboard: define the outcomes that matter and review them weekly.

- Film review: do call reviews, demo reps, and design reviews.

- Pre-mortems: before launches, ask how this fails.

- Post-mortems: after misses, write down what changes.

- Role clarity: keep the spikes sharp.

This is how pressure comes from the mission.

Not from politics.

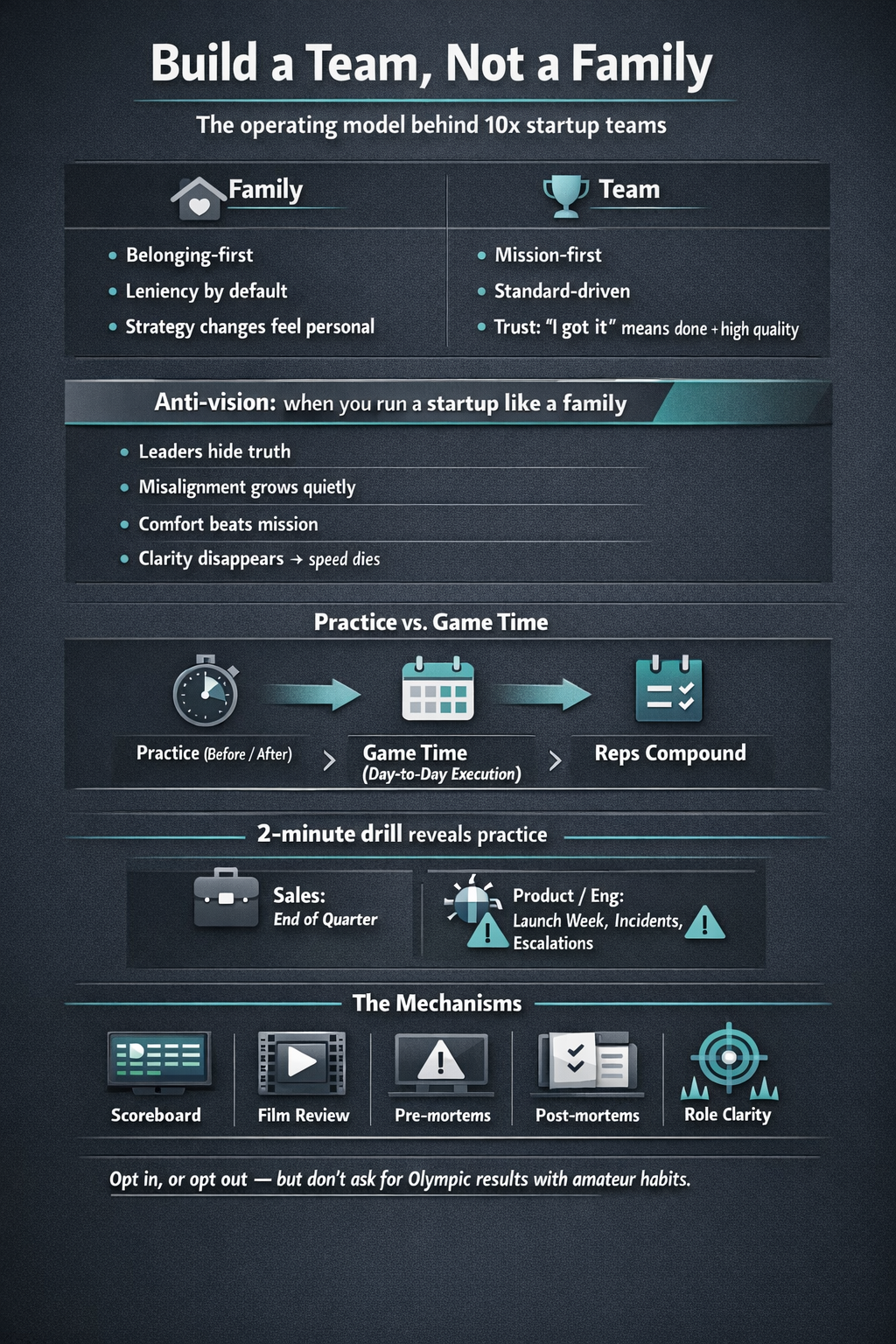

Quick recap (one visual)

If you want the entire operating model in one place, here it is:

XIII: A real example: talent density at Clubhouse

One of the best examples I can pull from my own life was Clubhouse.

What made it special wasn’t just the hype.

It was the speed of global adoption, the step-change in valuation, and the funding velocity that came with it.

That kind of pull only happens when the team is truly best in class.

From 2020 through 2021, as we scaled from roughly 13 people to the first 50, the talent density was different.

Everyone moved relentlessly toward outcomes.

If something broke, people showed up.

No after-hours excuses.

No convincing.

Just ownership.

Many of those people have since gone on to build the next generation of technology across OpenAI, Anthropic, and their own startups.

True pioneers across their vertical, industry, or craft.

XIV: The opt-in

This is not for everyone.

And that’s okay.

But do not ask for Olympic results with amateur habits.

Do not say you want to change the status quo while living by the rules of the status quo.

The real question is simple:

Do you actually want to be best in class?

Do you want to work around people who are best in class?

Do you want to be on a team where the baseline keeps rising?

Because this is not just a hiring standard.

It’s an opt-in.

For how you work.

For how you lead.

For what you tolerate.

And this is the part I remind myself of when things get messy.

In the middle of the chaos.

In the middle of the compromises.

Am I still building the team I would want to be on?

Am I protecting the standard?

Or just protecting comfort?

Because the hardest part of building elite teams is not setting the bar.

It’s remembering every day to live by it.

And then choosing, again and again, to opt in.

Check out the original post on X or the LinkedIn version.

Keep Reading

First Day of the Year: Reflect. Refine. Execute.

January 1 is the one day each year that feels universally quieter. That makes it the perfect day for reflection. Here's my annual ritual.

Three Things I'm Doing To Prevent Being In Between Jobs

Layoffs are still in full swing. Here's what I'm doing to prepare myself while I still have a job — so I'm never caught off guard.

7 Ways to Create an Amazing Follow-Up Email & Stand Out After the Interview

Most people think interviews are done after they meet. This is wrong. Here's how spending 15 minutes on a follow-up email can take you from 'top 3' to 'the one.'